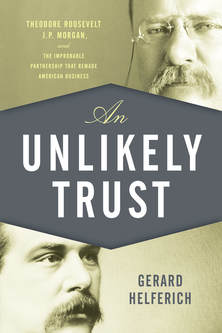

An Unlikely Trust: Theodore Roosevelt, J. P. Morgan, and the Improbable Partnership That Remade American Business

At the dawn of the twentieth century, Theodore Roosevelt and J. Pierpont Morgan were the two most powerful men in America, perhaps the world. As the nation’s preeminent financier, Morgan presided over an elemental shift in American business, away from family-owned companies and toward modern corporations of unparalleled size and influence. As president, Theodore Roosevelt expanded the power of that office to an unprecedented degree, seeking to rein in those corporations and to rebalance their interests with those of workers, consumers, and society at large.

Overpowering figures and titanic personalities, Roosevelt and Morgan could easily have become sworn enemies. And when they have been considered together (never before at book length), they have generally been portrayed as battling colossi, the great trust builder versus the original trustbuster. But their long association was far more complex than that.

Despite their many differences in temperament and philosophy, Roosevelt and Morgan had much in common—social class, an unstinting Victorian moralism, a drive for power, a need for order, and a genuine (though not purely altruistic) concern for the welfare of the nation. Working this common ground, the premier progressive and the quintessential capitalist were able to accomplish what neither could have achieved alone—including, more than once, averting national disaster. In the process they also changed the way that government and business worked together.

An Unlikely Trust is the story of the uneasy but historic collaboration between Theodore Roosevelt and Pierpont Morgan. It is also the story of how government and business evolved from a relationship of laissez-faire to the active regulation that we know today. And it is an account of how, despite all that has changed in America over the past century, so much remains the same, including the growing divide between rich and poor; the tangled bonds uniting politicians and business leaders; and the pervasive feeling that government is working for the special interests rather than for the people. Not least of all, it is the story of how two citizens with vastly disparate outlooks and interests managed to come together for the good of their common country.

Lyons Press, 2017, 288 pp., $26.95 hardcover

Praise for An Unlikely Trust

"A hostile commander-in-chief and a titan of American finance make a far-reaching peace in this colorful study of government-business relations in the Progressive Era.... Roosevelt delivers the thunder here, but the canny and understated Morgan becomes a fascinating protagonist as he conjures up money and strong-arms bankers to save Wall Street from destruction.... Helferich’s narrative has a lucid, light touch on the period’s economics and foregrounds the human element in white-knuckle crises and negotiations."

--Publishers Weekly

"This illuminating work about the partnership between President Theodore Roosevelt and John Pierpont Morgan is long overdue....Based on extensive research, this book fills a niche in the understanding of the complex relationship between Roosevelt and Morgan....Recommended for all who have an interest in business history or Roosevelt."

-- Library Journal

“An outstanding work of scholarship…. An Unlikely Trust brilliantly illuminates how these two giants of American history, both New Yorkers, found ways to work together during key episodes of the Roosevelt presidency…. An indispensable account…so intelligently crafted that there were times when I couldn’t put it down.”

--Clay S. Jenkinson, founder of the Theodore Roosevelt Center, principal scholar-consultant to the Theodore Roosevelt Presidential Library, and author of A Free and Hardy Life: Theodore Roosevelt’s Sojourn in the American West.

“In his well-researched and highly readable new book…Helferich shows how instead of demonizing each other, these two giants of the era set aside their equally-giant-sized egos to work for the benefit of the nation.”

--Edward P. Kohn, editor of A Most Glorious Ride: The Diaries of Theodore Roosevelt, 1877-1886

“Well researched and well written…American history told as a great story.”

--John M. Hilpert, author of American Cyclone: Theodore Roosevelt and His 1900 Whistlestop Campaign

“One of those rare chronicles of American business that brings its subjects to life….brilliantly highlights an often uneasy relationship between two larger-than-life leaders which did so much to shape the twentieth century.”

--J. Lee Annis Jr., author of Howard Baker: Conciliator in an Age of Crisis

“At a time when Americans are again struggling to figure out the right relationship between business and government, An Unlikely Trust is extraordinarily relevant.”

--Paul Aron, author of Founding Feuds and We Hold These Truths

Excerpt from the Prologue of An Unlikely Trust

Prologue

“This, Then, Is the Place to Stop This Trouble”

Sunday, November 3, 1907

It was 9:00 p.m. when a figure in a dark overcoat stepped out of

a cab at Madison Avenue and Thirty-Sixth Street. The young man was

big-boned, but his face was thin and topped by dark, oiled hair parted in

the middle. At age thirty-four, Ben Strong was already secretary of Bankers

Trust. Though founded just four years earlier, Bankers had grown into one

of the nation’s largest trust companies, thanks in part to its close ties with

Pierpont Morgan. But after the events of the past two weeks, a job at a

trust company, even a solvent one like Bankers, hardly seemed something

to brag about among Strong’s neighbors in Greenwich, Connecticut.

Gripping his briefcase, Strong stepped onto the sidewalk and strode

toward the long, low building before him. Designed by Charles McKim

in a serene, neoclassical style, it had been completed the year before, with

blocks of white marble dressed so perfectly that mortar had not been

needed. Mr. Morgan’s “library,” as it was known, had been conceived to

house the fabulous collection of artwork and manuscripts the financier

had amassed during his many journeys to Europe. Situated next to Morgan’s

three-story, ivy-covered townhouse, the library also functioned as

a private study. These days, at age seventy, the banker rarely went to the

offices of J.P. Morgan & Company, at 23 Wall Street, but worked a couple

of hours here every day, whenever he was in New York.

But tonight the library was hardly a place of refuge. On the sidewalk,

beyond the iron railing, clustered dozens of men whose notebooks and

cheap coats marked them as reporters. They had been planted here for

two weeks, ever since Mr. Morgan had rushed back from the Triennial

Episcopal Convention in Richmond, where as a lay delegate from the

Diocese of New York, he had immersed himself in the business before

the Church.

As Strong left the cab, reporters’ heads turned in his direction. All

evening, some of the most prominent bankers and businessmen in New

York, and that meant some of the most prominent in the world, had been

dashing in and out of these premises. Coal, steel, and railroad magnate

Henry Clay Frick had already arrived, as had Elbert H. Gary, chairman

of U.S. Steel. Seeing that the young man wasn’t a familiar figure among

this august company, the reporters turned away. Strong passed up the

low steps, between the pair of carved lionesses, past the marble columns,

through the massive bronze doors, and into the sumptuous rotunda.

He was unprepared for the pandemonium that greeted him. Everywhere,

it seemed, men were in motion, gesticulating, pacing the patterned

marble floor, oblivious to the antique statuary, the mosaic panels, the

frescoed ceilings. To Strong’s left the foyer opened onto the West Room,

Mr. Morgan’s study, with its red silk wall coverings and its wooden ceiling

imported from Italy. To his right, in the East Room, tall bookcases

housed some of the rarest masterworks of world literature. Directly

before him, at the rear of the rotunda, was a smaller door, surmounted

by an ancient marble statue of the Christ Child and the Virgin Mary,

with the carved inscription Soli Deo Honor et Gloria, “Honor and Glory

to God Alone.” Behind that door, in the office of his beautiful librarian,

Belle da Costa Greene, Mr. Morgan would be conferring with a few

trusted lieutenants and indulging in back-to-back games of solitaire, his

customary diversion in times of trouble. In defiance of his heavy cold and

the directives of Dr. Markoe, he was also chain smoking his huge Cuban

cigars, though in a nod to medical convention, he had promised to limit

himself to just twenty a day.

As Strong paused, he saw three men stride across the rotunda. He

recognized Gary, along with two colleagues from U.S. Steel, William J.

Filbert and Lewis Cass Ledyard. The heavy wooden door of the librarian’s

office opened to admit them, then abruptly shut again.

Strong was approached by Harry Davison, the forty-year-old

cofounder of Bankers Trust. As Strong’s employer, Davison had nominated

him for this exceptional and unnerving assignment. Now, for the

first time since the crisis began, Strong saw discouragement clouding his

mentor’s handsome, open features. Davison told him why: Mr. Morgan

had concluded that many more millions would be needed to prop up the

city’s failing trust companies and brokerage houses and, not incidentally,

forestall a collapse of the nation’s financial system. And it was needed

before the markets opened at ten o’clock tomorrow morning.

Strong entered the spacious West Room, where the bankers were

milling beneath ancient stained-glass windows, Renaissance paintings of

the saints, and a portrait of Pierpont’s father, Junius. In the far corner of

the room, its door ajar, was the vault where Mr. Morgan kept his priceless

manuscripts—letters written by George Washington, texts by Robert

Burns and Lord Byron, manuscripts by Beethoven and Mozart. A log

was burning in the huge carved stone fireplace, and on the mantel rested

an enamel plaque bearing Mr. Morgan’s personal motto: Pense moult,

Parle peu, Écris rien: “Think much, say little, write nothing.”

As the men conferred, an occasional messenger burst in from the

Waldorf-Astoria, a few blocks away on Fifth Avenue and Thirty-Third

Street, where the boards of the Trust Company of America and the

Lincoln Trust were meeting in emergency session. Bank executives continued

to arrive in waves; by 9:30, fifty had gathered in the West Room.

At 10:45, the door to the librarian’s office opened, and Elbert Gary and

Henry Frick strode through the rotunda and out of the building. As they

climbed into Frick’s car, they were mobbed by newsmen. The dapper

Gary gave a wan smile and told them, “I can’t say anything. I can’t talk.

I’d like to, but I can’t.” Later, Oakleigh Thorne, president of the Trust

Company of America, emerged and confessed to reporters, “I wish to

God I could tell what is going to happen.”

As the evening deepened, more bankers appeared at the library, until

a hundred men were pacing and smoking in the study, a stunning assemblage

that only Pierpont Morgan could have convened. At midnight,

Edwin Marsten, president of the Farmers’ Loan and Trust Company, was

called into the librarian’s office. When he returned, after nearly an hour,

his expression was grim. There had been an unexpected development, he

announced, apart from the crisis in the trust companies. He was not at

liberty to disclose its nature, but its resolution would require at least an

additional $25 million in funds. Mr. Morgan was prepared to step in, but

only if the presidents of the solvent trust companies could raise another

$25 million among themselves, to rescue their faltering colleagues. A

look of consternation passed from face to face.

Strong settled in a red velvet lounge chair, beside a man with thinning

hair and a thick salt-and-pepper mustache: James Stillman, president of

National City Bank, the nation’s largest. No sooner had Strong seated

himself than he dozed off. When he stirred, Stillman asked when he had

last been to bed. Thursday, Strong said; this would make his third night

in a row without sleep. Stillman suggested that the country wouldn’t

“smash” if he went home and got some rest. But just then the door to

the librarian’s office opened again, and the young banker was summoned.

Leaving the comfort of his lounge chair, he quit the West Room, crossed

the cool marble of the rotunda, and entered the sanctum sanctorum.

Photo Gallery from An Unlikely Trust

Overpowering figures and titanic personalities, Roosevelt and Morgan could easily have become sworn enemies. And when they have been considered together (never before at book length), they have generally been portrayed as battling colossi, the great trust builder versus the original trustbuster. But their long association was far more complex than that.

Despite their many differences in temperament and philosophy, Roosevelt and Morgan had much in common—social class, an unstinting Victorian moralism, a drive for power, a need for order, and a genuine (though not purely altruistic) concern for the welfare of the nation. Working this common ground, the premier progressive and the quintessential capitalist were able to accomplish what neither could have achieved alone—including, more than once, averting national disaster. In the process they also changed the way that government and business worked together.

An Unlikely Trust is the story of the uneasy but historic collaboration between Theodore Roosevelt and Pierpont Morgan. It is also the story of how government and business evolved from a relationship of laissez-faire to the active regulation that we know today. And it is an account of how, despite all that has changed in America over the past century, so much remains the same, including the growing divide between rich and poor; the tangled bonds uniting politicians and business leaders; and the pervasive feeling that government is working for the special interests rather than for the people. Not least of all, it is the story of how two citizens with vastly disparate outlooks and interests managed to come together for the good of their common country.

Lyons Press, 2017, 288 pp., $26.95 hardcover

Praise for An Unlikely Trust

"A hostile commander-in-chief and a titan of American finance make a far-reaching peace in this colorful study of government-business relations in the Progressive Era.... Roosevelt delivers the thunder here, but the canny and understated Morgan becomes a fascinating protagonist as he conjures up money and strong-arms bankers to save Wall Street from destruction.... Helferich’s narrative has a lucid, light touch on the period’s economics and foregrounds the human element in white-knuckle crises and negotiations."

--Publishers Weekly

"This illuminating work about the partnership between President Theodore Roosevelt and John Pierpont Morgan is long overdue....Based on extensive research, this book fills a niche in the understanding of the complex relationship between Roosevelt and Morgan....Recommended for all who have an interest in business history or Roosevelt."

-- Library Journal

“An outstanding work of scholarship…. An Unlikely Trust brilliantly illuminates how these two giants of American history, both New Yorkers, found ways to work together during key episodes of the Roosevelt presidency…. An indispensable account…so intelligently crafted that there were times when I couldn’t put it down.”

--Clay S. Jenkinson, founder of the Theodore Roosevelt Center, principal scholar-consultant to the Theodore Roosevelt Presidential Library, and author of A Free and Hardy Life: Theodore Roosevelt’s Sojourn in the American West.

“In his well-researched and highly readable new book…Helferich shows how instead of demonizing each other, these two giants of the era set aside their equally-giant-sized egos to work for the benefit of the nation.”

--Edward P. Kohn, editor of A Most Glorious Ride: The Diaries of Theodore Roosevelt, 1877-1886

“Well researched and well written…American history told as a great story.”

--John M. Hilpert, author of American Cyclone: Theodore Roosevelt and His 1900 Whistlestop Campaign

“One of those rare chronicles of American business that brings its subjects to life….brilliantly highlights an often uneasy relationship between two larger-than-life leaders which did so much to shape the twentieth century.”

--J. Lee Annis Jr., author of Howard Baker: Conciliator in an Age of Crisis

“At a time when Americans are again struggling to figure out the right relationship between business and government, An Unlikely Trust is extraordinarily relevant.”

--Paul Aron, author of Founding Feuds and We Hold These Truths

Excerpt from the Prologue of An Unlikely Trust

Prologue

“This, Then, Is the Place to Stop This Trouble”

Sunday, November 3, 1907

It was 9:00 p.m. when a figure in a dark overcoat stepped out of

a cab at Madison Avenue and Thirty-Sixth Street. The young man was

big-boned, but his face was thin and topped by dark, oiled hair parted in

the middle. At age thirty-four, Ben Strong was already secretary of Bankers

Trust. Though founded just four years earlier, Bankers had grown into one

of the nation’s largest trust companies, thanks in part to its close ties with

Pierpont Morgan. But after the events of the past two weeks, a job at a

trust company, even a solvent one like Bankers, hardly seemed something

to brag about among Strong’s neighbors in Greenwich, Connecticut.

Gripping his briefcase, Strong stepped onto the sidewalk and strode

toward the long, low building before him. Designed by Charles McKim

in a serene, neoclassical style, it had been completed the year before, with

blocks of white marble dressed so perfectly that mortar had not been

needed. Mr. Morgan’s “library,” as it was known, had been conceived to

house the fabulous collection of artwork and manuscripts the financier

had amassed during his many journeys to Europe. Situated next to Morgan’s

three-story, ivy-covered townhouse, the library also functioned as

a private study. These days, at age seventy, the banker rarely went to the

offices of J.P. Morgan & Company, at 23 Wall Street, but worked a couple

of hours here every day, whenever he was in New York.

But tonight the library was hardly a place of refuge. On the sidewalk,

beyond the iron railing, clustered dozens of men whose notebooks and

cheap coats marked them as reporters. They had been planted here for

two weeks, ever since Mr. Morgan had rushed back from the Triennial

Episcopal Convention in Richmond, where as a lay delegate from the

Diocese of New York, he had immersed himself in the business before

the Church.

As Strong left the cab, reporters’ heads turned in his direction. All

evening, some of the most prominent bankers and businessmen in New

York, and that meant some of the most prominent in the world, had been

dashing in and out of these premises. Coal, steel, and railroad magnate

Henry Clay Frick had already arrived, as had Elbert H. Gary, chairman

of U.S. Steel. Seeing that the young man wasn’t a familiar figure among

this august company, the reporters turned away. Strong passed up the

low steps, between the pair of carved lionesses, past the marble columns,

through the massive bronze doors, and into the sumptuous rotunda.

He was unprepared for the pandemonium that greeted him. Everywhere,

it seemed, men were in motion, gesticulating, pacing the patterned

marble floor, oblivious to the antique statuary, the mosaic panels, the

frescoed ceilings. To Strong’s left the foyer opened onto the West Room,

Mr. Morgan’s study, with its red silk wall coverings and its wooden ceiling

imported from Italy. To his right, in the East Room, tall bookcases

housed some of the rarest masterworks of world literature. Directly

before him, at the rear of the rotunda, was a smaller door, surmounted

by an ancient marble statue of the Christ Child and the Virgin Mary,

with the carved inscription Soli Deo Honor et Gloria, “Honor and Glory

to God Alone.” Behind that door, in the office of his beautiful librarian,

Belle da Costa Greene, Mr. Morgan would be conferring with a few

trusted lieutenants and indulging in back-to-back games of solitaire, his

customary diversion in times of trouble. In defiance of his heavy cold and

the directives of Dr. Markoe, he was also chain smoking his huge Cuban

cigars, though in a nod to medical convention, he had promised to limit

himself to just twenty a day.

As Strong paused, he saw three men stride across the rotunda. He

recognized Gary, along with two colleagues from U.S. Steel, William J.

Filbert and Lewis Cass Ledyard. The heavy wooden door of the librarian’s

office opened to admit them, then abruptly shut again.

Strong was approached by Harry Davison, the forty-year-old

cofounder of Bankers Trust. As Strong’s employer, Davison had nominated

him for this exceptional and unnerving assignment. Now, for the

first time since the crisis began, Strong saw discouragement clouding his

mentor’s handsome, open features. Davison told him why: Mr. Morgan

had concluded that many more millions would be needed to prop up the

city’s failing trust companies and brokerage houses and, not incidentally,

forestall a collapse of the nation’s financial system. And it was needed

before the markets opened at ten o’clock tomorrow morning.

Strong entered the spacious West Room, where the bankers were

milling beneath ancient stained-glass windows, Renaissance paintings of

the saints, and a portrait of Pierpont’s father, Junius. In the far corner of

the room, its door ajar, was the vault where Mr. Morgan kept his priceless

manuscripts—letters written by George Washington, texts by Robert

Burns and Lord Byron, manuscripts by Beethoven and Mozart. A log

was burning in the huge carved stone fireplace, and on the mantel rested

an enamel plaque bearing Mr. Morgan’s personal motto: Pense moult,

Parle peu, Écris rien: “Think much, say little, write nothing.”

As the men conferred, an occasional messenger burst in from the

Waldorf-Astoria, a few blocks away on Fifth Avenue and Thirty-Third

Street, where the boards of the Trust Company of America and the

Lincoln Trust were meeting in emergency session. Bank executives continued

to arrive in waves; by 9:30, fifty had gathered in the West Room.

At 10:45, the door to the librarian’s office opened, and Elbert Gary and

Henry Frick strode through the rotunda and out of the building. As they

climbed into Frick’s car, they were mobbed by newsmen. The dapper

Gary gave a wan smile and told them, “I can’t say anything. I can’t talk.

I’d like to, but I can’t.” Later, Oakleigh Thorne, president of the Trust

Company of America, emerged and confessed to reporters, “I wish to

God I could tell what is going to happen.”

As the evening deepened, more bankers appeared at the library, until

a hundred men were pacing and smoking in the study, a stunning assemblage

that only Pierpont Morgan could have convened. At midnight,

Edwin Marsten, president of the Farmers’ Loan and Trust Company, was

called into the librarian’s office. When he returned, after nearly an hour,

his expression was grim. There had been an unexpected development, he

announced, apart from the crisis in the trust companies. He was not at

liberty to disclose its nature, but its resolution would require at least an

additional $25 million in funds. Mr. Morgan was prepared to step in, but

only if the presidents of the solvent trust companies could raise another

$25 million among themselves, to rescue their faltering colleagues. A

look of consternation passed from face to face.

Strong settled in a red velvet lounge chair, beside a man with thinning

hair and a thick salt-and-pepper mustache: James Stillman, president of

National City Bank, the nation’s largest. No sooner had Strong seated

himself than he dozed off. When he stirred, Stillman asked when he had

last been to bed. Thursday, Strong said; this would make his third night

in a row without sleep. Stillman suggested that the country wouldn’t

“smash” if he went home and got some rest. But just then the door to

the librarian’s office opened again, and the young banker was summoned.

Leaving the comfort of his lounge chair, he quit the West Room, crossed

the cool marble of the rotunda, and entered the sanctum sanctorum.

Photo Gallery from An Unlikely Trust

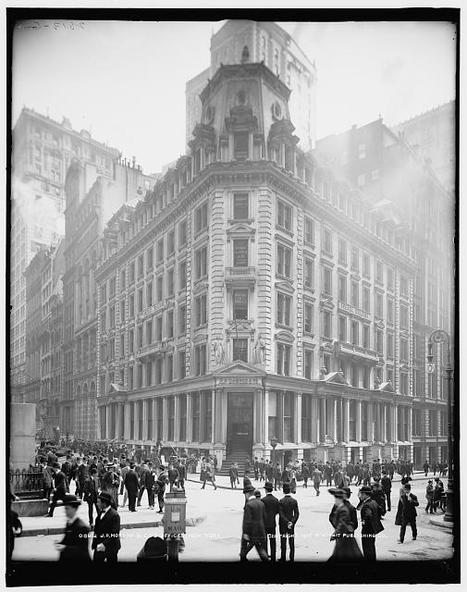

The elegant Drexel Building, home of J.P. Morgan & Company. Located at 23 Wall Street, "the Corner" was for decades the most storied business address in the world. (Library of Congress)

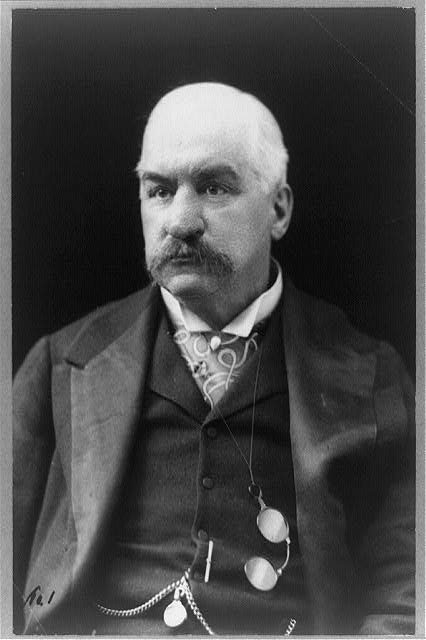

J. Pierpont Morgan. The most powerful man in America, he was called, more influential than the president himself. (Library of Congress)

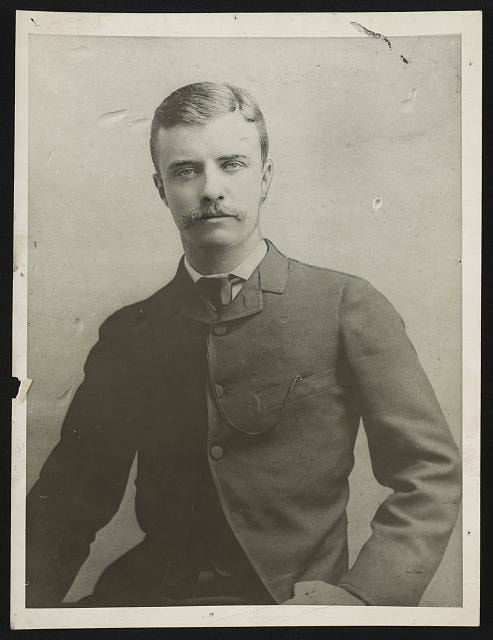

Theodore Roosevelt during his tenure as "the Cyclone Assemblyman" from Manhattan's 21st District. J. P. Morgan was among the earliest donors to Roosevelt's campaigns. (Library of Congress)

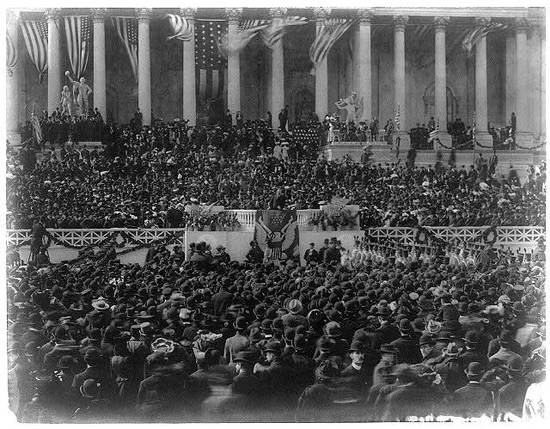

Roosevelt's second inauguration, March 4, 1905. The night before, he told a friend, “Tomorrow I shall come into my office in my own right. Then watch out for me.” (Library of Congress)

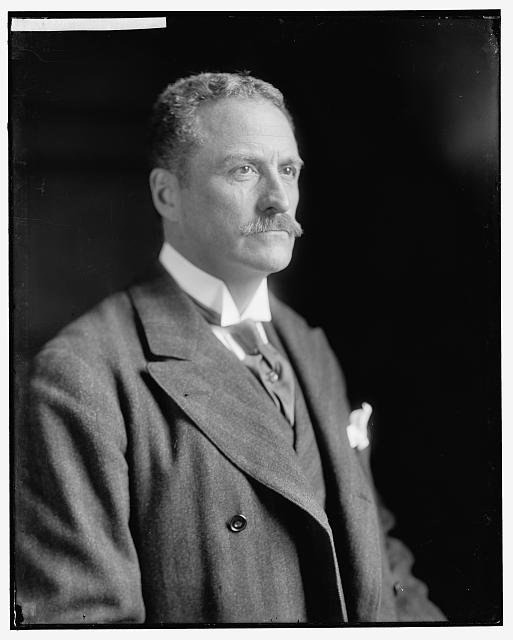

Morgan partner George W. Perkins. As Morgan's principal liaison with the Roosevelt Administration, Perkins was known as Morgan's "secretary of state." (Library of Congress)

Robert Bacon, lifetime friend of Theodore Roosevelt and business partner of Pierpont Morgan. Along with George Perkins, Bacon was a principal liaison between the White House and 23 Wall Street. (Library of Congress)

Morgan, accompanied by his son, Jack, and his daughter Louisa, arrives to testify before Congress's Pujo Committee, charged with investigating the banking industry. Morgan's masterful performance before the committee was, as one reporter put it, "dominating and not yet domineering." (Library of Congress)

Related Links

Theodore Roosevelt Center

Morgan Library and Museum

Chronicling America

Related Links

Theodore Roosevelt Center

Morgan Library and Museum

Chronicling America