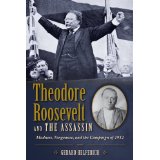

New York Times E-book Bestseller

Theodore Roosevelt and the Assassin: Madness, Vengeance, and the Campaign of 1912

It’s autumn 1912, and America is embroiled in a bitter presidential race that historians have called the most thrilling election in U.S. history. On the campaign trail, an assassin is stalking the most revered man in America.

After two brilliant presidential terms, Theodore Roosevelt declined to run for reelection in 1908, citing the long-standing tradition against any president being voted into a third term of office. But four years later, believing that his handpicked successor, William Howard Taft, has betrayed his progressive principles, Roosevelt takes the extraordinary step of challenging the incumbent for his party’s nomination. Though TR wins nine out of twelve primaries, the Republican convention nominates Taft on the first ballot.

Charging that the nomination has been stolen, Roosevelt makes the most risky (some would say foolhardy) decision of his political life and founds the Progressive, or “Bull Moose,” Party to contest the election. Besides Taft, he is opposed by the progressive Democrat Woodrow Wilson and the Socialist Eugene V. Debs. But exploiting his enormous energy and charm, Roosevelt dominates the campaign, crisscrossing the country on a ferocious whistle-stop tour and addressing huge crowds.

Meanwhile, in Lower Manhattan, a German-born, naturalized citizen named John Schrank is obsessed with the unfolding election. Not only does the fanatical loner find the ex-president’s campaign for a third term un-American, but he is convinced that the candidate’s extremism will thrust the country back into civil war and leave it vulnerable to foreign invasion. Answering what he believes to be a divine summons, Schrank buys a revolver and for the next month stalks Roosevelt across eight southern and midwestern states. Three times, in Atlanta, Chattanooga, and Chicago, the would-be assassin comes within striking distance but fails. Then, in Milwaukee, on the evening of October 14, Schrank confronts Roosevelt again.

Theodore Roosevelt and the Assassin is a day-by-day, minute-by-minute nonfiction account of the audacious attempt on Roosevelt’s life. Based on original sources including police interrogations, eyewitness testimony, and newspaper reports, the book is above all a fast-paced, suspenseful narrative. Drawing from Schrank’s own statements and writings, it also provides a chilling glimpse into the mind of a political assassin. Rich with local color and period detail, it transports the reader to the American heartland during a pivotal moment in our history, when the forces of progressivism and conservatism were battling for the nation’s soul--and joining the debate that, a century later, continues to shape American politics.

Lyons Press, 2013, 304 pp., $28.95 hardcover, $18.95 paperback

Praise for Theodore Roosevelt and the Assassin

"Immensely readable, entertaining….The book is hard to put down. Mr. Helferich's narrative structure recalls a number of recent popular histories that recount world-historical events from the perspective of a marginal figure, most notably Erik Larson's best-selling "The Devil in the White City" (2003)…. Mark Twain called Theodore Roosevelt "the most popular human being that has ever existed in the United States," and Mr. Helferich reinforces that notion as he moves his story along, depicting the "Colonel" cavorting with the common man on the campaign trail…. Yet what is striking in the book is Mr. Helferich's measured characterization of Schrank and vivid descriptions of his delusional mind…. Poor mad John Flammang Schrank, an assassin manqué—but for Gerard Helferich's literary efforts, lost to history…." --Wall Street Journal

"Onetime New York landlord and saloonkeeper John Schrank didn’t manage to join the club that decades later included Lee Harvey Oswald. But put him on the list with the likes of Squeaky Fromme and John Hinckley. Schrank took a shot at Teddy Roosevelt after stalking him, following the president’s whistle-stop tour around the country. The gunman believed Roosevelt had a hand in President McKinley’s murder in 1901 and that his campaign for a third term was an abuse of power. A fast-paced look at a little-remembered piece of history." --New York Post

"A lively account of Theodore Roosevelt’s would-be murder reveals the roiling issues and personalities of that key campaign....

In this light-pedaling, accessible study, Helferich (Stone of Kings: In Search of the Lost Jade of the Maya, 2011, etc.) creates several wonderful character studies: of Roosevelt, whom he calls either the Colonel or 'the third termer,' to designate the focus of Schrank’s rage against him in putting himself up for election to a third (nonconsecutive) term; of the much-maligned incumbent President William Howard Taft, Roosevelt’s handpicked successor who was so cowed by the anxiety of influence that he could not exert his own will in his own term and, when the wildly popular Roosevelt resolved to challenge him for the Republican nomination, fell out with him in an ugly, public battle; and of Schrank, a friendless landlord with accumulated grievances who believed Roosevelt’s hubris and unchecked ambition to run for a third term was a gross abuse of tried-and-true democratic institutions. Moreover, Helferich examines a dream that Schrank supposedly had that convinced him of Roosevelt’s conniving in McKinley’s murder and lent some truth to the court’s assumption that Schrank was delusional.

Outsized personalities within a blistering campaign render this work a rollicking history lesson." --Kirkus Reviews

“One doesn’t have to be a serious student of third-party politics or of Roosevelt’s try for a third presidential term to enjoy this minute-by-minute nonfiction account of the audacious assassination attempt on his life as the Bull Moose candidate…. Rich with local color and period detail [Theodore Roosevelt and the Assassin] transports the reader to a pivotal moment in our history, when the forces of progressivism and conservatism were battling for the nation’s soul.” —Delta

“Theodore Roosevelt--Rough Rider, Nobel Prize winner, builder of the Panama Canal--ranks as one of America’s most beloved presidents. Yet often forgotten is how close one man came to murdering him. In his vivid and richly detailed narrative, Gerard Helferich transports readers to the presidential campaign of 1912 when, in the shadows of a truly historic election, a would-be assassin silently tracked ‘Bull Moose’ Roosevelt and shot him. The result is a compelling and chilling work that brings to life this overlooked chapter of the TR legend.”

--Scott Miller, author of The President and the Assassin: McKinley, Terror, and Empire at the Dawn of the American Century

“Skillfully weaving together the heated debate of a critical election and the riveting tale of a stalking assassin, Helferich's is the rare book that both educates and entertains the reader. This gripping drama affirms Theodore Roosevelt's 1912 Progressive Party campaign as one of the most important and entertaining chapters in American political history.” --Sidney M. Milkis, University of Virginia

“Theodore Roosevelt—with his ‘take-no-prisoners’ approach—dominated the political life of the nation. Heir to a fortune, a know-it-all Harvard graduate, a righteous reformer with fierce opinions and unshakable confidence—he attracted passionate followers and equally passionate haters. This book is a compelling read about the historic 1912 presidential campaign, and the madman from a New York City saloon who was obsessed with derailing Teddy’s third term.”

--Richard Zacks, author of Island of Vice: Theodore Roosevelt’s Quest to Clean Up Sin-Loving New York

“Gerard Helferich has brilliantly made the past come alive.”

–Anton Community Newspapers (Long Island, NY)

“It’s a fascinating story expertly told by Gerard Helferich....[The book] is a fast-paced, thrilling read. The narrative provides fascinating insight into the mind of the would-be killer and details his twisted plans as they unfolded. Helferich’s greatest achievement is that he was able to create such a page-turner without sacrificing the historical details that make this story so interesting.” --Yazoo (MS) Herald

Excerpt from Theodore Roosevelt and the Assassin

Prologue

“Avenge My Death!”

Sunday, September 15, 1901

The young, heavyset man found himself alone in a cavernous room. Eerily quiet, the dim chamber was crowded with wreaths and sprays of flowers exuding an overpowering, syrupy odor. In the center of the room rested an open coffin of polished Santo Domingo mahogany. Inside the casket lay a portly, middle-aged man dressed in a black suit, a white shirt with a stiff collar, and a slender black bow tie. The man’s thinning gray hair was oiled, revealing a high forehead, owlish brows, and a square, cleft chin. Even in death, the features wore a stolid but kindly expression, revealing no trace of malice, no hint of the suffering he’d endured. The young man recognized the face immediately. It belonged to President William McKinley, who had perished early the previous morning.

For the past week, the young man had pored over the newspapers, immersing himself in the details of the tragedy. The president had been attending the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, a lavish spectacle meant to showcase American prosperity at the dawn of the twentieth century, with fanciful lagoons and canals, a midway of rides and attractions, and massive exhibition halls dedicated to sciences such as agriculture and mining, all bathed in electric light from the newly harnessed power of Niagara Falls. But while Buffalo had begun to call itself “the City of Light,” its exposition would forever after be linked with something dark and hideous.

The fair had opened in May, and President McKinley had planned to make an official visit in June. But when the First Lady had another of her “attacks,” the trip was postponed until September.

The president finally arrived in Buffalo on Wednesday the fourth, and the following day delivered a fine speech on one of his pet themes, the need to expand overseas markets for American goods. On Friday, declared President’s Day at the exposition, he boarded a train to view the spectacular Falls, twenty miles away, then returned to Buffalo and prepared to greet the public at the exposition’s Temple of Music. Fearing for his chief’s safety in the throng, McKinley’s personal secretary had canceled the reception twice, but the president had insisted on attending. “No one would wish to hurt me,” he’d scoffed. Besides, the president enjoyed meeting the public. “Everyone in that line has a smile and a cheery word,” he said. “They bring no problems with them; only good will.”

William McKinley had coasted to reelection less than a year before, on the slogan “Prosperity at Home and Prestige Abroad.” The economy had finally recovered from the Panic of 1893, the worst financial depression the nation had ever seen. Thanks to its swift, seemingly effortless victory in the Spanish-American War, the country had won strategic possessions in the Caribbean and the Pacific and had joined the ranks of the world’s great powers. By the time the Temple of Music’s doors opened at 4:00 p.m., a queue had been waiting for hours to shake the popular president’s hand.

The Temple was the exposition’s principal auditorium, designed in the Italian Renaissance style and set beside the fair’s central Fountain of Abundance. The exterior was painted soft yellow, trimmed with red and gold, and topped by a sky-blue dome. At each of the building’s four corners opened a graceful arched doorway, surmounted by a plaster statue representing a different musical genre. Outside the east entrance this afternoon, waiting with the rest of the crowd under the warm September sun, stood a mill worker named Leon Czolgosz.

Born in Michigan, the son of Polish immigrants, the twenty-eight-year-old Czolgosz had lived most of his life in McKinley’s home state of Ohio. He’d arrived in Buffalo the week before and had registered in a rooming house under the name Fred Nieman, saying he’d come to sell souvenirs at the fair, though none of the other boarders had noticed any evidence of mercantile activity. Keeping to himself, the newcomer seemed to spend most of his time hunched over the daily newspapers.

Several years ago, after losing his job during a strike at a Cleveland wire mill, Czolgosz had been drawn to the radical philosophy of anarchism. Dedicated to fomenting revolution and establishing an egalitarian and stateless society, anarchists subscribed to the “propaganda of the deed,” the belief that the most potent way to advance their cause was through spectacular acts of violence such as bombings and assassinations. Over the past two decades, anarchists had orchestrated dozens of acts of terrorism, especially in Europe, where they had killed Russian Czar Alexander II, French President Marie François Sadi Carnot, Spanish Prime Minister Antonio Cánovas del Castillo, and, just the year before, King Umberto I of Italy.

The United States had also seen two presidents assassinated over the past thirty-six years. But the first, Abraham Lincoln, had been a casualty of civil war. And the other, James Garfield, had been shot by a lunatic named Charles Guiteau, who thought to claim the presidency for himself. Neither of these domestic assassins was an anarchist, wishing to abolish all government. Yet even as Americans celebrated the new century, the nation was deeply divided. Over the past several decades, as the country had grown more industrial, more urban, and more ethnically diverse, huge monopolistic “trusts” such as John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil and J. P. Morgan’s U.S. Steel had come to dominate the nation’s commerce and, increasingly, its politics, until it seemed that the interests of the wealthy and powerful had eclipsed the needs of working people. And into this broken soil were sown the fertile seeds of anarchy.

William McKinley was a child of the middle class, but his election campaign had been underwritten by millionaires and corporations, and as president he had served those interests well. He advocated steep tariffs to protect American companies, even though the levies meant higher prices for consumers. And though he assured workers that they too would benefit from the expanding economy, the lion’s share of the gains had gone to investors. Over the past few decades, as new machines had decreased the demand for labor and as waves of European immigrants had increased the supply, factory employees had watched their wages fall, even as their hours remained long and their working conditions hazardous. In case after case, the Supreme Court had ruled against workers and in favor of capitalists. And if employees dared to strike, they were apt to be brutalized by private security forces, the police, or the Army, and then discarded for new, even more desperate recruits willing to work for less. In the words of “the Great Commoner,” William Jennings Bryan, who had run against McKinley in 1896, “The extremes of society, [were] being driven further and further apart.”

Leon Czolgosz had felt labor injustice firsthand, and after hearing the anarchist Emma Goldman address a rally in Chicago, he had determined to act. The day before, when McKinley had delivered his speech at the Pan-American Exhibition, Czolgosz had been standing in the throng, but he hadn’t been able to shoulder his way close to the president. Reading in one of his newspapers that McKinley would spend this morning at Niagara Falls, Czolgosz had shadowed him there, but again unable to get near, he had taken an early train back to Buffalo. That same afternoon, he was among the first in line outside the Temple of Music.

At four o’clock, when the doors opened, the president stood beneath the Temple’s soaring dome, flanked by an enormous American flag and a display of potted plants, while a Bach sonata wafted from the new pipe organ. Then, as the public began filing past the cordon of soldiers, a dark-skinned, “foreign-looking” man attracted the suspicion of guards, who were on the alert for anarchists. Concern mounted when the man persisted in pumping the president’s hand for an unseemly time before finally being led away. In the confusion, no one noticed Leon Czolgosz, with his right hand jammed into his coat pocket.

The line of greeters inched forward, and Czolgosz reached the president’s side at 4:07. McKinley smiled, and the anarchist withdrew his hand, swathed in a white handkerchief. Inside was a silver-plated, .32-calibre Johnson revolver, the same model that had been used to kill Umberto I.

Two explosions shook the Temple’s dome. Then a heavy silence descended. A look of confusion spread over McKinley’s face, and a sudden pallor. He slumped but didn’t collapse. Guards and bystanders began pummeling the shooter. But as the president was helped away, he said, “Don’t let them hurt him.”

“I done my duty,” Czolgosz was heard to say.

With blood seeping onto his white shirt and vest, McKinley was carried by an electric ambulance to the exposition’s hospital. Like most of the fair buildings, and even the spectacular Temple of Music, the low, mission-style hospital was a temporary construction of a plaster-like material called staff, destined to be demolished after the exhibition’s six-month run. But whereas the public venues were bathed in brilliant light, the infirmary hadn’t been fitted with electricity. To inspect the president’s wound, doctors rigged a hospital pan to reflect the late-afternoon sun.

One slug had been deflected by the president’s sternum.The other had entered the left side of his body, about five inches below the breast. Probing the wound with bare, unsterilized fingers, the doctors were unable to locate the bullet.

As it happened, Buffalo’s leading expert on gunshot wounds had been called away to Niagara Falls on another case, so officials summoned a gynecological surgeon named Matthew Mann from a nearby barbershop where he was having his hair trimmed. Arriving at the fairgrounds with his head half shorn, Mann stitched the president together as best he could and decided not to risk removing the projectile.

As news of the shooting spread, the nation crowded into houses of worship to pray for its stricken leader. Newspapers reported that McKinley was resting comfortably at the home of exposition president John G. Milburn, and after four days he was pronounced out of danger. Reassured, Vice President Theodore Roosevelt, who’d been called to Buffalo, left for a family camping vacation in the Adirondacks.

Then, on the afternoon of September 12, McKinley’s pulse abruptly weakened, and he began to drift in and out of consciousness. On the evening of the thirteenth, a telegram went out to Roosevelt: “The president appears to be dying and members of the cabinet in Buffalo think you should lose no time coming.” And so the vice president began a headlong journey to Buffalo, thirteen hours away by buckboard and special train. En route, he muttered of Czolgosz, “If it had been I who had been shot, he wouldn’t have got away so easily. . . . I’d have guzzled him first.”

That night, the president glanced about his sickroom and murmured, “God’s will be done, not ours.” The First Lady leaned close and sang his favorite hymn, “Nearer, My God, to Thee.” Then, at 2:15 on the morning of September 14, the fifty-eight-year-old McKinley expired. The autopsy showed that the bullet had sliced through his stomach, pancreas, and a kidney, before lodging deep in his back; the cause of death was gangrene.

Now, as the young man stood over McKinley’s coffin, he saw the serene expression drain from the president’s face. McKinley stirred in his casket and sat straight as a lamppost. He narrowed his sharp, dark eyes and extended a waxy finger toward a corner of the room. The young man followed the president’s gaze. Against the wall, a shadowy figure was cowering in the coarse robes of a Catholic monk. The young man expected to see the lean features of poor Leon Czolgosz, still bruised from his beating. But this was an older face, wide and fierce, all spectacles and teeth.

The young man sat up in bed, his breathing ragged. At this hour, there was no clip-clop of horses’ hooves from the Manhattan streets, no clang of church bells, no sound at all. Peering at his watch, he saw that it was nearly two o’clock.

Hours later, when the first thin, gray light seeped over the East River, the words the president had spoken still ricocheted through his brain: “This is my murderer and nobody else! Avenge my death!”

And he could still see the figure skulking in the shadows near the presidential casket: Gazing from beneath the monk’s cowl had been the smirking face of Theodore Roosevelt.

After two brilliant presidential terms, Theodore Roosevelt declined to run for reelection in 1908, citing the long-standing tradition against any president being voted into a third term of office. But four years later, believing that his handpicked successor, William Howard Taft, has betrayed his progressive principles, Roosevelt takes the extraordinary step of challenging the incumbent for his party’s nomination. Though TR wins nine out of twelve primaries, the Republican convention nominates Taft on the first ballot.

Charging that the nomination has been stolen, Roosevelt makes the most risky (some would say foolhardy) decision of his political life and founds the Progressive, or “Bull Moose,” Party to contest the election. Besides Taft, he is opposed by the progressive Democrat Woodrow Wilson and the Socialist Eugene V. Debs. But exploiting his enormous energy and charm, Roosevelt dominates the campaign, crisscrossing the country on a ferocious whistle-stop tour and addressing huge crowds.

Meanwhile, in Lower Manhattan, a German-born, naturalized citizen named John Schrank is obsessed with the unfolding election. Not only does the fanatical loner find the ex-president’s campaign for a third term un-American, but he is convinced that the candidate’s extremism will thrust the country back into civil war and leave it vulnerable to foreign invasion. Answering what he believes to be a divine summons, Schrank buys a revolver and for the next month stalks Roosevelt across eight southern and midwestern states. Three times, in Atlanta, Chattanooga, and Chicago, the would-be assassin comes within striking distance but fails. Then, in Milwaukee, on the evening of October 14, Schrank confronts Roosevelt again.

Theodore Roosevelt and the Assassin is a day-by-day, minute-by-minute nonfiction account of the audacious attempt on Roosevelt’s life. Based on original sources including police interrogations, eyewitness testimony, and newspaper reports, the book is above all a fast-paced, suspenseful narrative. Drawing from Schrank’s own statements and writings, it also provides a chilling glimpse into the mind of a political assassin. Rich with local color and period detail, it transports the reader to the American heartland during a pivotal moment in our history, when the forces of progressivism and conservatism were battling for the nation’s soul--and joining the debate that, a century later, continues to shape American politics.

Lyons Press, 2013, 304 pp., $28.95 hardcover, $18.95 paperback

Praise for Theodore Roosevelt and the Assassin

"Immensely readable, entertaining….The book is hard to put down. Mr. Helferich's narrative structure recalls a number of recent popular histories that recount world-historical events from the perspective of a marginal figure, most notably Erik Larson's best-selling "The Devil in the White City" (2003)…. Mark Twain called Theodore Roosevelt "the most popular human being that has ever existed in the United States," and Mr. Helferich reinforces that notion as he moves his story along, depicting the "Colonel" cavorting with the common man on the campaign trail…. Yet what is striking in the book is Mr. Helferich's measured characterization of Schrank and vivid descriptions of his delusional mind…. Poor mad John Flammang Schrank, an assassin manqué—but for Gerard Helferich's literary efforts, lost to history…." --Wall Street Journal

"Onetime New York landlord and saloonkeeper John Schrank didn’t manage to join the club that decades later included Lee Harvey Oswald. But put him on the list with the likes of Squeaky Fromme and John Hinckley. Schrank took a shot at Teddy Roosevelt after stalking him, following the president’s whistle-stop tour around the country. The gunman believed Roosevelt had a hand in President McKinley’s murder in 1901 and that his campaign for a third term was an abuse of power. A fast-paced look at a little-remembered piece of history." --New York Post

"A lively account of Theodore Roosevelt’s would-be murder reveals the roiling issues and personalities of that key campaign....

In this light-pedaling, accessible study, Helferich (Stone of Kings: In Search of the Lost Jade of the Maya, 2011, etc.) creates several wonderful character studies: of Roosevelt, whom he calls either the Colonel or 'the third termer,' to designate the focus of Schrank’s rage against him in putting himself up for election to a third (nonconsecutive) term; of the much-maligned incumbent President William Howard Taft, Roosevelt’s handpicked successor who was so cowed by the anxiety of influence that he could not exert his own will in his own term and, when the wildly popular Roosevelt resolved to challenge him for the Republican nomination, fell out with him in an ugly, public battle; and of Schrank, a friendless landlord with accumulated grievances who believed Roosevelt’s hubris and unchecked ambition to run for a third term was a gross abuse of tried-and-true democratic institutions. Moreover, Helferich examines a dream that Schrank supposedly had that convinced him of Roosevelt’s conniving in McKinley’s murder and lent some truth to the court’s assumption that Schrank was delusional.

Outsized personalities within a blistering campaign render this work a rollicking history lesson." --Kirkus Reviews

“One doesn’t have to be a serious student of third-party politics or of Roosevelt’s try for a third presidential term to enjoy this minute-by-minute nonfiction account of the audacious assassination attempt on his life as the Bull Moose candidate…. Rich with local color and period detail [Theodore Roosevelt and the Assassin] transports the reader to a pivotal moment in our history, when the forces of progressivism and conservatism were battling for the nation’s soul.” —Delta

“Theodore Roosevelt--Rough Rider, Nobel Prize winner, builder of the Panama Canal--ranks as one of America’s most beloved presidents. Yet often forgotten is how close one man came to murdering him. In his vivid and richly detailed narrative, Gerard Helferich transports readers to the presidential campaign of 1912 when, in the shadows of a truly historic election, a would-be assassin silently tracked ‘Bull Moose’ Roosevelt and shot him. The result is a compelling and chilling work that brings to life this overlooked chapter of the TR legend.”

--Scott Miller, author of The President and the Assassin: McKinley, Terror, and Empire at the Dawn of the American Century

“Skillfully weaving together the heated debate of a critical election and the riveting tale of a stalking assassin, Helferich's is the rare book that both educates and entertains the reader. This gripping drama affirms Theodore Roosevelt's 1912 Progressive Party campaign as one of the most important and entertaining chapters in American political history.” --Sidney M. Milkis, University of Virginia

“Theodore Roosevelt—with his ‘take-no-prisoners’ approach—dominated the political life of the nation. Heir to a fortune, a know-it-all Harvard graduate, a righteous reformer with fierce opinions and unshakable confidence—he attracted passionate followers and equally passionate haters. This book is a compelling read about the historic 1912 presidential campaign, and the madman from a New York City saloon who was obsessed with derailing Teddy’s third term.”

--Richard Zacks, author of Island of Vice: Theodore Roosevelt’s Quest to Clean Up Sin-Loving New York

“Gerard Helferich has brilliantly made the past come alive.”

–Anton Community Newspapers (Long Island, NY)

“It’s a fascinating story expertly told by Gerard Helferich....[The book] is a fast-paced, thrilling read. The narrative provides fascinating insight into the mind of the would-be killer and details his twisted plans as they unfolded. Helferich’s greatest achievement is that he was able to create such a page-turner without sacrificing the historical details that make this story so interesting.” --Yazoo (MS) Herald

Excerpt from Theodore Roosevelt and the Assassin

Prologue

“Avenge My Death!”

Sunday, September 15, 1901

The young, heavyset man found himself alone in a cavernous room. Eerily quiet, the dim chamber was crowded with wreaths and sprays of flowers exuding an overpowering, syrupy odor. In the center of the room rested an open coffin of polished Santo Domingo mahogany. Inside the casket lay a portly, middle-aged man dressed in a black suit, a white shirt with a stiff collar, and a slender black bow tie. The man’s thinning gray hair was oiled, revealing a high forehead, owlish brows, and a square, cleft chin. Even in death, the features wore a stolid but kindly expression, revealing no trace of malice, no hint of the suffering he’d endured. The young man recognized the face immediately. It belonged to President William McKinley, who had perished early the previous morning.

For the past week, the young man had pored over the newspapers, immersing himself in the details of the tragedy. The president had been attending the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, a lavish spectacle meant to showcase American prosperity at the dawn of the twentieth century, with fanciful lagoons and canals, a midway of rides and attractions, and massive exhibition halls dedicated to sciences such as agriculture and mining, all bathed in electric light from the newly harnessed power of Niagara Falls. But while Buffalo had begun to call itself “the City of Light,” its exposition would forever after be linked with something dark and hideous.

The fair had opened in May, and President McKinley had planned to make an official visit in June. But when the First Lady had another of her “attacks,” the trip was postponed until September.

The president finally arrived in Buffalo on Wednesday the fourth, and the following day delivered a fine speech on one of his pet themes, the need to expand overseas markets for American goods. On Friday, declared President’s Day at the exposition, he boarded a train to view the spectacular Falls, twenty miles away, then returned to Buffalo and prepared to greet the public at the exposition’s Temple of Music. Fearing for his chief’s safety in the throng, McKinley’s personal secretary had canceled the reception twice, but the president had insisted on attending. “No one would wish to hurt me,” he’d scoffed. Besides, the president enjoyed meeting the public. “Everyone in that line has a smile and a cheery word,” he said. “They bring no problems with them; only good will.”

William McKinley had coasted to reelection less than a year before, on the slogan “Prosperity at Home and Prestige Abroad.” The economy had finally recovered from the Panic of 1893, the worst financial depression the nation had ever seen. Thanks to its swift, seemingly effortless victory in the Spanish-American War, the country had won strategic possessions in the Caribbean and the Pacific and had joined the ranks of the world’s great powers. By the time the Temple of Music’s doors opened at 4:00 p.m., a queue had been waiting for hours to shake the popular president’s hand.

The Temple was the exposition’s principal auditorium, designed in the Italian Renaissance style and set beside the fair’s central Fountain of Abundance. The exterior was painted soft yellow, trimmed with red and gold, and topped by a sky-blue dome. At each of the building’s four corners opened a graceful arched doorway, surmounted by a plaster statue representing a different musical genre. Outside the east entrance this afternoon, waiting with the rest of the crowd under the warm September sun, stood a mill worker named Leon Czolgosz.

Born in Michigan, the son of Polish immigrants, the twenty-eight-year-old Czolgosz had lived most of his life in McKinley’s home state of Ohio. He’d arrived in Buffalo the week before and had registered in a rooming house under the name Fred Nieman, saying he’d come to sell souvenirs at the fair, though none of the other boarders had noticed any evidence of mercantile activity. Keeping to himself, the newcomer seemed to spend most of his time hunched over the daily newspapers.

Several years ago, after losing his job during a strike at a Cleveland wire mill, Czolgosz had been drawn to the radical philosophy of anarchism. Dedicated to fomenting revolution and establishing an egalitarian and stateless society, anarchists subscribed to the “propaganda of the deed,” the belief that the most potent way to advance their cause was through spectacular acts of violence such as bombings and assassinations. Over the past two decades, anarchists had orchestrated dozens of acts of terrorism, especially in Europe, where they had killed Russian Czar Alexander II, French President Marie François Sadi Carnot, Spanish Prime Minister Antonio Cánovas del Castillo, and, just the year before, King Umberto I of Italy.

The United States had also seen two presidents assassinated over the past thirty-six years. But the first, Abraham Lincoln, had been a casualty of civil war. And the other, James Garfield, had been shot by a lunatic named Charles Guiteau, who thought to claim the presidency for himself. Neither of these domestic assassins was an anarchist, wishing to abolish all government. Yet even as Americans celebrated the new century, the nation was deeply divided. Over the past several decades, as the country had grown more industrial, more urban, and more ethnically diverse, huge monopolistic “trusts” such as John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil and J. P. Morgan’s U.S. Steel had come to dominate the nation’s commerce and, increasingly, its politics, until it seemed that the interests of the wealthy and powerful had eclipsed the needs of working people. And into this broken soil were sown the fertile seeds of anarchy.

William McKinley was a child of the middle class, but his election campaign had been underwritten by millionaires and corporations, and as president he had served those interests well. He advocated steep tariffs to protect American companies, even though the levies meant higher prices for consumers. And though he assured workers that they too would benefit from the expanding economy, the lion’s share of the gains had gone to investors. Over the past few decades, as new machines had decreased the demand for labor and as waves of European immigrants had increased the supply, factory employees had watched their wages fall, even as their hours remained long and their working conditions hazardous. In case after case, the Supreme Court had ruled against workers and in favor of capitalists. And if employees dared to strike, they were apt to be brutalized by private security forces, the police, or the Army, and then discarded for new, even more desperate recruits willing to work for less. In the words of “the Great Commoner,” William Jennings Bryan, who had run against McKinley in 1896, “The extremes of society, [were] being driven further and further apart.”

Leon Czolgosz had felt labor injustice firsthand, and after hearing the anarchist Emma Goldman address a rally in Chicago, he had determined to act. The day before, when McKinley had delivered his speech at the Pan-American Exhibition, Czolgosz had been standing in the throng, but he hadn’t been able to shoulder his way close to the president. Reading in one of his newspapers that McKinley would spend this morning at Niagara Falls, Czolgosz had shadowed him there, but again unable to get near, he had taken an early train back to Buffalo. That same afternoon, he was among the first in line outside the Temple of Music.

At four o’clock, when the doors opened, the president stood beneath the Temple’s soaring dome, flanked by an enormous American flag and a display of potted plants, while a Bach sonata wafted from the new pipe organ. Then, as the public began filing past the cordon of soldiers, a dark-skinned, “foreign-looking” man attracted the suspicion of guards, who were on the alert for anarchists. Concern mounted when the man persisted in pumping the president’s hand for an unseemly time before finally being led away. In the confusion, no one noticed Leon Czolgosz, with his right hand jammed into his coat pocket.

The line of greeters inched forward, and Czolgosz reached the president’s side at 4:07. McKinley smiled, and the anarchist withdrew his hand, swathed in a white handkerchief. Inside was a silver-plated, .32-calibre Johnson revolver, the same model that had been used to kill Umberto I.

Two explosions shook the Temple’s dome. Then a heavy silence descended. A look of confusion spread over McKinley’s face, and a sudden pallor. He slumped but didn’t collapse. Guards and bystanders began pummeling the shooter. But as the president was helped away, he said, “Don’t let them hurt him.”

“I done my duty,” Czolgosz was heard to say.

With blood seeping onto his white shirt and vest, McKinley was carried by an electric ambulance to the exposition’s hospital. Like most of the fair buildings, and even the spectacular Temple of Music, the low, mission-style hospital was a temporary construction of a plaster-like material called staff, destined to be demolished after the exhibition’s six-month run. But whereas the public venues were bathed in brilliant light, the infirmary hadn’t been fitted with electricity. To inspect the president’s wound, doctors rigged a hospital pan to reflect the late-afternoon sun.

One slug had been deflected by the president’s sternum.The other had entered the left side of his body, about five inches below the breast. Probing the wound with bare, unsterilized fingers, the doctors were unable to locate the bullet.

As it happened, Buffalo’s leading expert on gunshot wounds had been called away to Niagara Falls on another case, so officials summoned a gynecological surgeon named Matthew Mann from a nearby barbershop where he was having his hair trimmed. Arriving at the fairgrounds with his head half shorn, Mann stitched the president together as best he could and decided not to risk removing the projectile.

As news of the shooting spread, the nation crowded into houses of worship to pray for its stricken leader. Newspapers reported that McKinley was resting comfortably at the home of exposition president John G. Milburn, and after four days he was pronounced out of danger. Reassured, Vice President Theodore Roosevelt, who’d been called to Buffalo, left for a family camping vacation in the Adirondacks.

Then, on the afternoon of September 12, McKinley’s pulse abruptly weakened, and he began to drift in and out of consciousness. On the evening of the thirteenth, a telegram went out to Roosevelt: “The president appears to be dying and members of the cabinet in Buffalo think you should lose no time coming.” And so the vice president began a headlong journey to Buffalo, thirteen hours away by buckboard and special train. En route, he muttered of Czolgosz, “If it had been I who had been shot, he wouldn’t have got away so easily. . . . I’d have guzzled him first.”

That night, the president glanced about his sickroom and murmured, “God’s will be done, not ours.” The First Lady leaned close and sang his favorite hymn, “Nearer, My God, to Thee.” Then, at 2:15 on the morning of September 14, the fifty-eight-year-old McKinley expired. The autopsy showed that the bullet had sliced through his stomach, pancreas, and a kidney, before lodging deep in his back; the cause of death was gangrene.

Now, as the young man stood over McKinley’s coffin, he saw the serene expression drain from the president’s face. McKinley stirred in his casket and sat straight as a lamppost. He narrowed his sharp, dark eyes and extended a waxy finger toward a corner of the room. The young man followed the president’s gaze. Against the wall, a shadowy figure was cowering in the coarse robes of a Catholic monk. The young man expected to see the lean features of poor Leon Czolgosz, still bruised from his beating. But this was an older face, wide and fierce, all spectacles and teeth.

The young man sat up in bed, his breathing ragged. At this hour, there was no clip-clop of horses’ hooves from the Manhattan streets, no clang of church bells, no sound at all. Peering at his watch, he saw that it was nearly two o’clock.

Hours later, when the first thin, gray light seeped over the East River, the words the president had spoken still ricocheted through his brain: “This is my murderer and nobody else! Avenge my death!”

And he could still see the figure skulking in the shadows near the presidential casket: Gazing from beneath the monk’s cowl had been the smirking face of Theodore Roosevelt.

Photo Gallery from Theodore Roosevelt and the Assassin

John Schrank, the would-be assassin who stalked Theodore Roosevelt through eight southern and midwestern states, looking for an opportunity to strike.

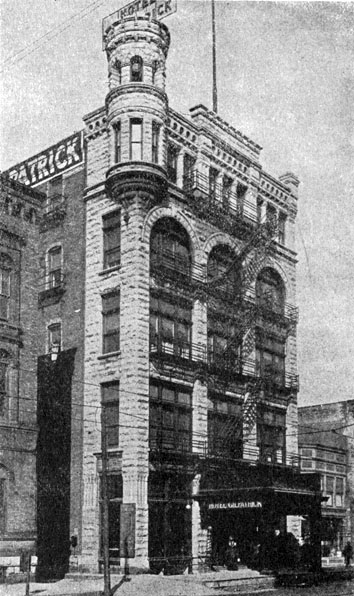

Milwaukee's Hotel Gilpatrick. When Theodore Roosevelt left on the night of October 14, 1912, on his way to address ten thousand supporters, John Schrank was waiting in the crowded street.

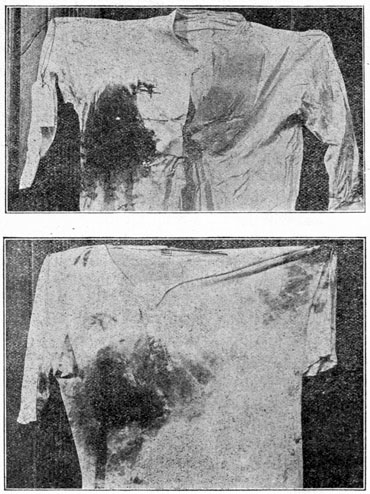

The bloody shirt and undershirt Roosevelt was wearing on the evening of October 14, 1912. The shirts, along with Schrank's .45-caliber Colt revolver, were introduced into evidence during his arraignment.