Stone of Kings: In Search of the Lost Jade of the Maya

Jade has long been prized as one of the most precious substances on earth, used to adorn kings, cure disease, and perform sacred rituals, including human sacrifice. For millennia, it played a crucial role in the culture of the Maya and other ancient Americans, but the Spanish lusted after gold and silver, and within fifty years of the Conquest, the source of Maya jade had been forgotten. Centuries later, archaeologists excavating Maya cities uncovered stunning jades carved with the images of gods and kings, evoking all the mystery and power of a bygone civilization. But where had the stone come from? Some guessed China, others Atlantis—but no one could say for sure, because for the only time in history, a civilization’s most valuable resource had been lost.

This is the story of the gripping, 400-year search for the lost sources of this precious stone. A vivid tale of great rulers, renowned archaeologists, gifted scientists, unlettered prospectors, and hopeful entrepreneurs, Stone of Kings melds history, popular science, and armchair travel into a real-life, high-stakes treasure hunt for the astonishing Maya jade.

Lyons Press, 2012, 304 pages, $24.95 hardcover, $14.95 paperback

This is the story of the gripping, 400-year search for the lost sources of this precious stone. A vivid tale of great rulers, renowned archaeologists, gifted scientists, unlettered prospectors, and hopeful entrepreneurs, Stone of Kings melds history, popular science, and armchair travel into a real-life, high-stakes treasure hunt for the astonishing Maya jade.

Lyons Press, 2012, 304 pages, $24.95 hardcover, $14.95 paperback

Praise for Stone of Kings

“A compelling tale. . . . This well-focused and well-told account brings America's most mythologized gemstone into sharp relief.” --Wall Street Journal

Selected by the American Booksellers Association for the Indie Next List of recommended titles: “In the spirit of Indiana Jones, author Helferich takes us on an amazing journey through history and through the mountains of Guatemala in search of the lost jade of the Maya. If you relish great fireside tales of adventure or going into the jungles from your armchair, you’ll enjoy this book."

“This is an absorbing and exciting story about a stone that ancient Mesoamericans prized above gold. The search for the sources of this mysterious rock reads like detective fiction, and involves geologists, archaeologists, entrepreneurs, poachers, and a host of other characters, but it’s all true. A wonderful read!”

--Michael D. Coe, author of Breaking the Maya Code

"While others were anticipating the dubious 2012 Long Count apocalypse, Gerard Helferich was chasing an answer to a much more interesting Maya mystery—where had the legendary Maya jade come from? Stone of Kings is a rare creature in the world of adventure literature: equal parts fascinating travelogue, rich history, and good old-fashioned detective story. --Mark Adams, author of Turn Right at Machu Picchu

"Stone of Kings is an exciting story involving adventurers, geologists, archaeologists, entrepreneurs, looters, thieves, and a host of other characters. This nonfiction work reads like an adventure novel, with its fascinating cast of characters set in the wilds of Guatemala in the midst of a civil war. It is a perfect mix of science and adventure, of travelogue and history. Author Gerard Helferich has done a masterful job of capturing the drama and excitement of the hunt for ancient Mesoamerica’s most precious and elusive commodity." --American Archaeology, March 2012

“Stone of Kings is a well-written and fascinating book that tells the full story of Mesoamerican jade. In today’s world jade is a highly prized gemstone, but for the ancient Maya and other pre-Columbian Mesoamerica civilizations, jade was the most precious and powerful substance in the universe. Against the backdrop of the rise and fall of these civilizations, and a history of conquest, revolution, and civil war, Gerard Helferich describes how archaeologists, geologists, adventurers, and entrepreneurs rediscovered the long lost source of Mesoamerican jade. He also tells us how this discovery led to the rebirth of the art of jade carving in Guatemala, the original homeland of both jade and the Maya people.” --Robert Sharer, author of The Ancient Maya

“This is a delightful and exciting book. It has a perfect mix of science and adventure, plus a fascinating cast of real characters, the jade hunters themselves. Recommended to anyone who likes tales of archaeology mixed with adventure—and vice versa!”

--Arthur Demarest, author of Ancient Maya: The Rise and Fall of a Rainforest

Civilization

“In Stone of Kings, Gerard Helferich finally demystifies jade in the Americas. From the other-earthly blues of Olmec times to the apple-green translucent jades of the Classic Maya, this book is a gripping travelogue through time and the mysterious backcountry of Guatemala, where fabulous discoveries of this most exotic and highly treasured stone of the New World have recently been made.”

--David W. Sedat, Founding Director, the Copan 2012 Botanical Research Station

"Synthesizing the works of geologists, archaeologists, anthropologists, and historians, this book is a highly readable and fascinating description of the search for jade in Mesoamérica from ancient times to the present. Helferich intertwines this story skillfully with the political and economic history of Guatemala and with the crucial role that entrepreneurs Jay and Mary Lou Ridinger of Antigua Guatemala played in this process."

--Ralph Lee Woodward, author of A Short History of Guatemala

"An engrossing read that should be enjoyed by the general public and scholars alike."

--Jeremy A. Sabloff, President, Santa Fe Institute

"Helferich delivers a lively narrative, notwithstanding passages focused on the scientific minutiae underlying the Ridingers’ improbable success. Engaging cross-cultural tale of ancient peoples and modern desires." --Kirkus Reviews

Selected by the American Booksellers Association for the Indie Next List of recommended titles: “In the spirit of Indiana Jones, author Helferich takes us on an amazing journey through history and through the mountains of Guatemala in search of the lost jade of the Maya. If you relish great fireside tales of adventure or going into the jungles from your armchair, you’ll enjoy this book."

“This is an absorbing and exciting story about a stone that ancient Mesoamericans prized above gold. The search for the sources of this mysterious rock reads like detective fiction, and involves geologists, archaeologists, entrepreneurs, poachers, and a host of other characters, but it’s all true. A wonderful read!”

--Michael D. Coe, author of Breaking the Maya Code

"While others were anticipating the dubious 2012 Long Count apocalypse, Gerard Helferich was chasing an answer to a much more interesting Maya mystery—where had the legendary Maya jade come from? Stone of Kings is a rare creature in the world of adventure literature: equal parts fascinating travelogue, rich history, and good old-fashioned detective story. --Mark Adams, author of Turn Right at Machu Picchu

"Stone of Kings is an exciting story involving adventurers, geologists, archaeologists, entrepreneurs, looters, thieves, and a host of other characters. This nonfiction work reads like an adventure novel, with its fascinating cast of characters set in the wilds of Guatemala in the midst of a civil war. It is a perfect mix of science and adventure, of travelogue and history. Author Gerard Helferich has done a masterful job of capturing the drama and excitement of the hunt for ancient Mesoamerica’s most precious and elusive commodity." --American Archaeology, March 2012

“Stone of Kings is a well-written and fascinating book that tells the full story of Mesoamerican jade. In today’s world jade is a highly prized gemstone, but for the ancient Maya and other pre-Columbian Mesoamerica civilizations, jade was the most precious and powerful substance in the universe. Against the backdrop of the rise and fall of these civilizations, and a history of conquest, revolution, and civil war, Gerard Helferich describes how archaeologists, geologists, adventurers, and entrepreneurs rediscovered the long lost source of Mesoamerican jade. He also tells us how this discovery led to the rebirth of the art of jade carving in Guatemala, the original homeland of both jade and the Maya people.” --Robert Sharer, author of The Ancient Maya

“This is a delightful and exciting book. It has a perfect mix of science and adventure, plus a fascinating cast of real characters, the jade hunters themselves. Recommended to anyone who likes tales of archaeology mixed with adventure—and vice versa!”

--Arthur Demarest, author of Ancient Maya: The Rise and Fall of a Rainforest

Civilization

“In Stone of Kings, Gerard Helferich finally demystifies jade in the Americas. From the other-earthly blues of Olmec times to the apple-green translucent jades of the Classic Maya, this book is a gripping travelogue through time and the mysterious backcountry of Guatemala, where fabulous discoveries of this most exotic and highly treasured stone of the New World have recently been made.”

--David W. Sedat, Founding Director, the Copan 2012 Botanical Research Station

"Synthesizing the works of geologists, archaeologists, anthropologists, and historians, this book is a highly readable and fascinating description of the search for jade in Mesoamérica from ancient times to the present. Helferich intertwines this story skillfully with the political and economic history of Guatemala and with the crucial role that entrepreneurs Jay and Mary Lou Ridinger of Antigua Guatemala played in this process."

--Ralph Lee Woodward, author of A Short History of Guatemala

"An engrossing read that should be enjoyed by the general public and scholars alike."

--Jeremy A. Sabloff, President, Santa Fe Institute

"Helferich delivers a lively narrative, notwithstanding passages focused on the scientific minutiae underlying the Ridingers’ improbable success. Engaging cross-cultural tale of ancient peoples and modern desires." --Kirkus Reviews

Excerpt from Stone of Kings

Prologue

It’s a warm April evening on the cusp of the rainy season. We’re seated under the long, tiled colonnade of a centuries-old house in Antigua, in the highlands of Guatemala. My wife, Teresa, and I have come to do some research for a travel publisher. But as the shadows deepen and the volcanoes disappear into the darkness, our hostess begins to spin a remarkable tale.

A tall blonde gringa of a certain age, she is the sister of a friend back in our adopted home of San Miguel de Allende, Mexico. But you might say we were introduced by Alexander von Humboldt. A few years ago, our hostess’s husband read my Humboldt’s Cosmos, an account of the great German naturalist’s New World odyssey. As I relate in the book, Humboldt was born into an aristocratic Prussian family during the Second Great Age of Discovery, when titanic figures such as James Cook and Louis-Antoine de Bougainville were completing their historic circumnavigations of the earth. Though the young Alexander longed to make a grand journey of his own, his mother pressed him into a more sensible career as a government inspector of mines. But on coming into his fortune after his mother’s death, Humboldt persuaded King Carlos IV to entrust him—not yet thirty, a foreigner, and a Protestant—with the first extensive scientific exploration of Spain’s New World empire. And during five astonishing years, from 1799 to 1804, Humboldt and his companion Aimé Bonpland blazed a hazardous, six-thousand-mile swath through Latin America, from Cuba to Peru, from the Andes to the Amazon, opening the continent to science and transforming himself into one of the most celebrated figures of his age.

For reasons I don’t fully appreciate at the time, our hostess’s husband has been moved by Humboldt’s story, and he has invited me to drop by if I’m ever in Antigua. When Teresa and I arrive, he’s too ill to see us, but his wife graciously invites us for a drink. I expect a simple social call; then she begins her story. A story of jade. Like most people, I’ve never thought much about the stone—where it comes from, why it’s important or interesting, even what it is. But as her voice echoes down the darkening colonnade, I feel the mounting exhilaration of a writer encountering his subject.

When I return from Antigua, I begin reading about jade and pestering archaeologists and geologists, learning everything I can about its formation, its lore, its ties to the great cultures of the past. I also discover a connection I hadn’t expected. In Humboldt’s Cosmos, I wrote about his admiration for America’s native peoples and his pioneering studies of cultures such as the Aztec and the Inca. Among the tens of thousands of specimens Humboldt brought back at the end of his journey were some pre-Columbian figurines, one of which was reproduced in my book.

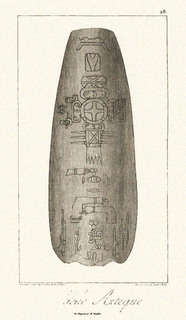

This time, my thoughts turn to another of Humboldt’s souvenirs. It’s a celt, a polished stone shaped vaguely like the head of an axe, which was presented to the explorer by Andrés Manuel del Río, professor of mineralogy at Mexico City’s national school of mining. Bluish in color, about nine inches long and a little better than three inches wide, the celt had lost its pointed end. But the rest was incised with a dozen rebus-like symbols. Though a few were recognizable—a pair of crossed arms, a hand, an ornate cross, perhaps an oar and a spear thrower—their significance was long forgotten. As Humboldt realized, the celt was carved from jade.

It’s a warm April evening on the cusp of the rainy season. We’re seated under the long, tiled colonnade of a centuries-old house in Antigua, in the highlands of Guatemala. My wife, Teresa, and I have come to do some research for a travel publisher. But as the shadows deepen and the volcanoes disappear into the darkness, our hostess begins to spin a remarkable tale.

A tall blonde gringa of a certain age, she is the sister of a friend back in our adopted home of San Miguel de Allende, Mexico. But you might say we were introduced by Alexander von Humboldt. A few years ago, our hostess’s husband read my Humboldt’s Cosmos, an account of the great German naturalist’s New World odyssey. As I relate in the book, Humboldt was born into an aristocratic Prussian family during the Second Great Age of Discovery, when titanic figures such as James Cook and Louis-Antoine de Bougainville were completing their historic circumnavigations of the earth. Though the young Alexander longed to make a grand journey of his own, his mother pressed him into a more sensible career as a government inspector of mines. But on coming into his fortune after his mother’s death, Humboldt persuaded King Carlos IV to entrust him—not yet thirty, a foreigner, and a Protestant—with the first extensive scientific exploration of Spain’s New World empire. And during five astonishing years, from 1799 to 1804, Humboldt and his companion Aimé Bonpland blazed a hazardous, six-thousand-mile swath through Latin America, from Cuba to Peru, from the Andes to the Amazon, opening the continent to science and transforming himself into one of the most celebrated figures of his age.

For reasons I don’t fully appreciate at the time, our hostess’s husband has been moved by Humboldt’s story, and he has invited me to drop by if I’m ever in Antigua. When Teresa and I arrive, he’s too ill to see us, but his wife graciously invites us for a drink. I expect a simple social call; then she begins her story. A story of jade. Like most people, I’ve never thought much about the stone—where it comes from, why it’s important or interesting, even what it is. But as her voice echoes down the darkening colonnade, I feel the mounting exhilaration of a writer encountering his subject.

When I return from Antigua, I begin reading about jade and pestering archaeologists and geologists, learning everything I can about its formation, its lore, its ties to the great cultures of the past. I also discover a connection I hadn’t expected. In Humboldt’s Cosmos, I wrote about his admiration for America’s native peoples and his pioneering studies of cultures such as the Aztec and the Inca. Among the tens of thousands of specimens Humboldt brought back at the end of his journey were some pre-Columbian figurines, one of which was reproduced in my book.

This time, my thoughts turn to another of Humboldt’s souvenirs. It’s a celt, a polished stone shaped vaguely like the head of an axe, which was presented to the explorer by Andrés Manuel del Río, professor of mineralogy at Mexico City’s national school of mining. Bluish in color, about nine inches long and a little better than three inches wide, the celt had lost its pointed end. But the rest was incised with a dozen rebus-like symbols. Though a few were recognizable—a pair of crossed arms, a hand, an ornate cross, perhaps an oar and a spear thrower—their significance was long forgotten. As Humboldt realized, the celt was carved from jade.

The enigmatic Humboldt Celt, as it appeared in Humboldt’s Researches Concerning the Institutions and Monuments of the Ancient Inhabitants of America with Descriptions and Views of Some of the Most Striking Scenes in the Cordilleras.

Back in Europe, Humboldt presented the artifact, which he believed to be an Aztec hatchet, to his sovereign, Frederick Wilhelm III of Prussia, for display in the royal cabinet of curiosities, a collection of natural history and anthropological specimens. For the next century and a half, the Humboldt Celt, as it came to be known, remained in Berlin. Though the stone’s message was inscribed in no known language, that didn’t stop a scholar named Philipp J. J. Valentini from venturing an impressively detailed translation in 1881:

"The man, in whose tomb the sacred stone was laid, stood high in rank and personal achievements. He never failed to appear before his gods to burn the incense on the temple’s brazier. He caused his arms to bleed and sacrificed his blood by sprinkling it in the glowing embers. When he entered the tlachco court, his was the victory. Like darts, his balls of hule were flying through the ring. He had no equal in bringing to the ground his foe by tlacoctli, and when he seized the oar and went upon the river, he was certain to bring home the sweet turtle quivering on the barb of his harpoon. Great was the strength of his arms; the heavy cudgel was the toy of his youth. There was no deer so distant nor its legs so fleet, that his eyes could not spy or his lasso reach."

Eventually, the celt ended up in the national ethnographic museum on Stresemannstrasse. When that building was destroyed during the Second World War, the Humboldt Celt—shattered, looted, or perhaps buried in the rubble—was lost.

As I immerse myself in my new subject, the errant celt takes on a meaning for me as well, more vague but perhaps no less idiosyncratic than that suggested by Philipp Valentini: With its strange carvings and unexplained disappearance, it seems to embody the enigma of jade.

To peoples such as the Maya, jade was not only heartbreakingly beautiful but supremely powerful, and no substance was more eagerly acquired or more jealously guarded. Yet when Alexander von Humboldt arrived in Latin America, a millennium after the Maya decline and three centuries after the Spanish Conquest, no one knew where the ancients had found their jade. Humboldt searched for the source, to no avail. “Notwithstanding our long and frequent excursions in the Cordillera of both Americas,” he wrote, “we were never able to discover a rock of jade; and this rock being so scarce, the more we were surprised at the immense quantity of jade hatchets, which are found on digging in plains formerly inhabited, from the Ohio to the mountains of Chile.” Humboldt exaggerated the range of jade artifacts, but by the time his keepsake went missing, the mystery of the stone’s origin still hadn’t been solved. Like the Humboldt Celt, the Maya’s jade mines had vanished.

The story that our hostess shares this evening in Antigua is of the long search for Maya jade. Part history, part science, part treasure hunt, the tale spans more than three thousand years, embracing great kings, lost civilizations, renowned archaeologists, unlettered prospectors, and hopeful entrepreneurs. It’s a tale of mystery and obsession, and I can’t escape its peculiar pull. Like all the others, I’m drawn into the quest for Maya jade.

Back in Europe, Humboldt presented the artifact, which he believed to be an Aztec hatchet, to his sovereign, Frederick Wilhelm III of Prussia, for display in the royal cabinet of curiosities, a collection of natural history and anthropological specimens. For the next century and a half, the Humboldt Celt, as it came to be known, remained in Berlin. Though the stone’s message was inscribed in no known language, that didn’t stop a scholar named Philipp J. J. Valentini from venturing an impressively detailed translation in 1881:

"The man, in whose tomb the sacred stone was laid, stood high in rank and personal achievements. He never failed to appear before his gods to burn the incense on the temple’s brazier. He caused his arms to bleed and sacrificed his blood by sprinkling it in the glowing embers. When he entered the tlachco court, his was the victory. Like darts, his balls of hule were flying through the ring. He had no equal in bringing to the ground his foe by tlacoctli, and when he seized the oar and went upon the river, he was certain to bring home the sweet turtle quivering on the barb of his harpoon. Great was the strength of his arms; the heavy cudgel was the toy of his youth. There was no deer so distant nor its legs so fleet, that his eyes could not spy or his lasso reach."

Eventually, the celt ended up in the national ethnographic museum on Stresemannstrasse. When that building was destroyed during the Second World War, the Humboldt Celt—shattered, looted, or perhaps buried in the rubble—was lost.

As I immerse myself in my new subject, the errant celt takes on a meaning for me as well, more vague but perhaps no less idiosyncratic than that suggested by Philipp Valentini: With its strange carvings and unexplained disappearance, it seems to embody the enigma of jade.

To peoples such as the Maya, jade was not only heartbreakingly beautiful but supremely powerful, and no substance was more eagerly acquired or more jealously guarded. Yet when Alexander von Humboldt arrived in Latin America, a millennium after the Maya decline and three centuries after the Spanish Conquest, no one knew where the ancients had found their jade. Humboldt searched for the source, to no avail. “Notwithstanding our long and frequent excursions in the Cordillera of both Americas,” he wrote, “we were never able to discover a rock of jade; and this rock being so scarce, the more we were surprised at the immense quantity of jade hatchets, which are found on digging in plains formerly inhabited, from the Ohio to the mountains of Chile.” Humboldt exaggerated the range of jade artifacts, but by the time his keepsake went missing, the mystery of the stone’s origin still hadn’t been solved. Like the Humboldt Celt, the Maya’s jade mines had vanished.

The story that our hostess shares this evening in Antigua is of the long search for Maya jade. Part history, part science, part treasure hunt, the tale spans more than three thousand years, embracing great kings, lost civilizations, renowned archaeologists, unlettered prospectors, and hopeful entrepreneurs. It’s a tale of mystery and obsession, and I can’t escape its peculiar pull. Like all the others, I’m drawn into the quest for Maya jade.

Photo Gallery from Stone of Kings

El Castillo before restoration, in a photo taken by Desiré Charnay around 1860. “Old and cold,” Edward H. Thompson wrote on seeing Chichen Itza’s ruins for the first time, “furrowed by time, and haggard, imposing, and impassive, they rear their rugged masses above the surrounding level and are beyond description.”

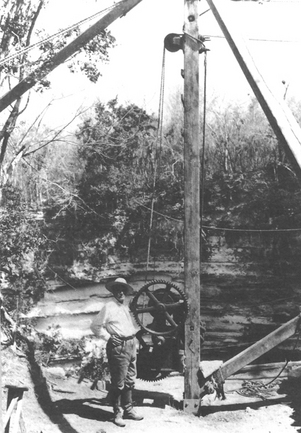

Edward H. Thompson with the dredge he erected over the Sacred Cenote at Chichen Itza. “I doubt if anybody can realize the thrill I felt, when, with four men at the winch handles and one at the brake, the dredge, with its steel jaw agape, swung from the platform, hung poised for a brief moment in mid-air over the dark pit and then, with a long swift glide downward, entered the still, dark waters and sank smoothly on its quest.”

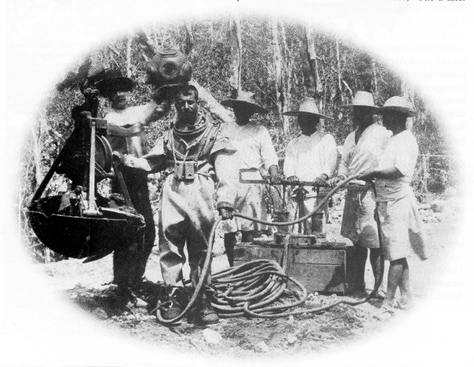

Edward H. Thompson in his diving gear at Chichen Itza, with his workers poised at the air pump. On his first dive into the cenote, Thompson wrote, “I felt a strange thrill when I realized that I was the only living being who had ever reached this place alive and expected to leave it again still living.”

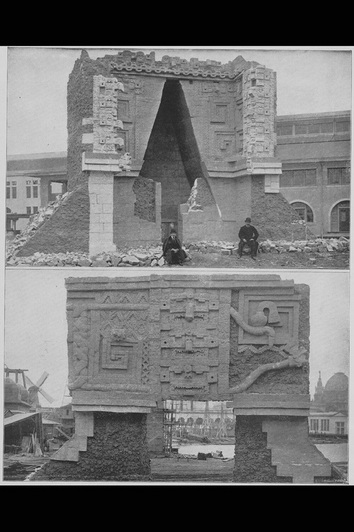

Two views of a structure reproduced from the ruins at Uxmal, part of the “Mayan Village” that was erected on the Midway of the 1893 World’s Columbia Exposition in Chicago, beside the Ferris wheel and Buffalo Bill’s Wild West.

The grave of the great Maya king Jasaw Chan K’awiil I, who revitalized the city-state of Tikal after his accession in A.D. 682, as reproduced in the Museo Nacional de Arqueología y Etnología in Guatemala City. Some of the jade beads are the size of small apples.

The area south of the Sierra de las Minas, one of the places where the Maya found their jade, is the only arid part of Guatemala and one of the driest regions in Central America, with only about twenty inches of rain a year.

Related Links

For more information on Mesoamerican jade, the Maya, the Olmecs, and other pre-Columbian peoples, try these web sites:

American Museum of Natural History. Information for the layperson and student on the geology of jade, including summaries of the latest research. www.amnh.org.

Archaeology magazine. Free online access to news briefs, reviews, and selected longer articles from 1996 to the present. www.archaeology.com.

Dumbarton Oaks. Illustrated online collection of pre-Columbian artifacts, including jades. www.doaks.org.

Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies. A wealth of information on the Maya, Olmecs, and other Mesoamerican peoples, including an extensive bibliography. www.famsi.org.

National Geographic Society. Free online access to illustrated articles on the Maya, Olmecs, and other pre-Hispanic peoples. www.naturalgeographic.com.

Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology at Harvard University. Illustrated online collection tion of pre-Columbian artifacts, including carved jades. www.peabody.harvard.edu.

Smithsonian magazine. Free online access to articles from the magazine, including those on the Maya and other ancient American civilizations. www.smithsonianmag.com.

Archaeology magazine. Free online access to news briefs, reviews, and selected longer articles from 1996 to the present. www.archaeology.com.

Dumbarton Oaks. Illustrated online collection of pre-Columbian artifacts, including jades. www.doaks.org.

Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies. A wealth of information on the Maya, Olmecs, and other Mesoamerican peoples, including an extensive bibliography. www.famsi.org.

National Geographic Society. Free online access to illustrated articles on the Maya, Olmecs, and other pre-Hispanic peoples. www.naturalgeographic.com.

Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology at Harvard University. Illustrated online collection tion of pre-Columbian artifacts, including carved jades. www.peabody.harvard.edu.

Smithsonian magazine. Free online access to articles from the magazine, including those on the Maya and other ancient American civilizations. www.smithsonianmag.com.